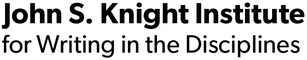

Cornell Writes! Tips from our community of writers is a digital newsletter sponsored by the Knight Institute for Writing in the Disciplines and the Cornell University Graduate School.

Each week, a member of our writing community – a Graduate Writing Service, English Language Support Office, or Cornell Writing Centers tutor; a writing specialist from the Knight Institute; a writing instructor from our First-Year Writing Seminars or Writing in the Majors programs; maybe YOU – will share a writing strategy from their own writer’s toolkit. #writelikeabear

Contact Tracy Hamler Carrick with questions and ideas.

Meet Kelly King-O'Brien

Hello Cornell Writers! My name is Kelly King-O’Brien, and I teach a few different writing courses–some based on the news, one based on post-WWII American history, plus an upper-level writing course. I also work with graduate students teaching writing, which I enjoy a great deal.

Here is this week’s Writing Tip!

These tips are geared towards revising a paper when you have a good draft, which might primarily involve sentence-level revisions. Email me if you have questions: kkobrien@cornell.edu. I hope these documents help you–they certainly have helped me!

When we receive feedback that our writing is unclear, often that means we need to work on sentence-level revisions such as verbs and subjects. Our verbs may be weak and lacking significant action and our subjects may be unclear or unrecognizable to readers.

Here is a easy-to-use checklist for writers to guide the sentence-level revision process, followed by supplementary materials that define terms and provide addional examples.

Revising your Prose: A Writer's Checklistfrom the Little Red School House curriculum, UChicago |

|

1. Identify your audience. More expert audiences will be able to tolerate more nominalizations, abstractions, and core violations. Less expert audiences may need to see actions in verbs, characters in subjects, and complete subject/verb "cores" near the beginning of sentences. Nominalizations= nouns that could be verbs. Investigation=investigate. Does the reader know who is doing what to whom if significant actions are expressed in nouns rather than verbs? Core violations=The subject and the verb are far apart in a sentence. Why is this a problem? Readers will get bogged down in individual sentences. Subjectively, they’ll feel as if they are waiting for the sentence to start. They have to restart the sentence several times; they may start skimming.

2. Who are the main characters, human, institutional, AND conceptual, in your argument? Make a list of the most important three or four or five. Characters=Grammatical subjects.

3. Skim down the beginning of each sentence: do your most important characters appear in the subject position of most sentences? If you find large blocks of sentences where none of these characters appear, you've found candidates for revision. The fix: See if you can focus the passage by putting one or more of your most important characters in the subjects of sentences.

4. In passages that seem complex and cumbersome, underline the number of words that appear before the first complete subject/verb core. If you've underlined more than half the sentence, you've found a candidate for revision. Core=A subject and a verb. The fix: put a complete subject/verb core at or near the beginning of most sentences. Why? Sentences seem easier to process when their subjects and verbs are up front and close together.

5. Find passages that make an argument or analyze complex information, and circle the connectors – words like if/then, because, and therefore. Readers may have trouble following your argument if there aren't many connectors, or if the connectors are too dilute to signal a precise logical relationship. Logical connectors=logic words that express a relationship between two subject-verb cores. The fix: If actions are hiding in nominalizations, unpack them into subject/verb cores. Then link these new cores with significant connectors that express a logical relationship:

Remember: not all nominalizations are bad! You need nominalizations in academic and research-oriented writing. On occasion, however, you can express the logic of your argument more directly if the structure of your sentence forces you to use more connectors. |

Supplemental Instruction of terms on the “Revising Your Prose” worksheet

1. NOMINALIZATIONS: Many experts use nominalizations in writing but in so doing, the action of the sentence takes place in a noun rather than a verb, which makes it harder for readers to process. Readers in English look for actions in verbs so if they don’t see that, they find the sentence unclear and are waiting around for the verb.

Example: (nominalizations in bold)

Original: Staff evaluation of the program will be conducted soon in order to achieve enhanced efficiency.

What if we changed the kind of word that expresses the action? That is, instead of expressing them as nouns, we express them in verbs. Also, who is doing what to whom?

Revised: The staff will soon evaluate the program so that they can serve their clients more efficiently.

Diagnostic #1: After you write a paper, circle your verbs and any nominalizations. Assess whether the verbs convey significant action to your readers. If not, consider revising. If you see a lot of nominalizations, ponder whether they obscure action. If so, consider changing them into action verbs and modifying the sentence as needed. Also, if you have a lot of weak verbs (like “is” or “occurring”) then your readers will likely find your writing unclear.

Sum up: Nominalizations are not unclear if you use them to name things. (If you are talking about an agreement such as a legal agreement, then it’s not unclear because you are naming a thing.) You can also use nominalizations to describe unimportant actions. However, writers (especially experts, perhaps unintentionally) use nominalizations to express important actions. If you mean the action of agreeing then you shouldn’t use agreement, because your readers are looking for verbs and instead they see the action in a noun, and thus your writing is harder to follow.

Tip: Use action verbs! Sample sheet at the end.

2. CHARACTERS: Instead of limiting ourselves to the traditional definition of subjects as “people, place, or thing,” the Little Red Schoolhouse encourages us to ponder using grammatical subjects that our readers value. When you become an expert in a field, you often know what those are because you are well-informed about the scholarship. A character is anything your readers take to be capable of acting or being acted upon. You may have previously been taught that “the subject of a sentence is the actor.” And this formula is often true, because many subjects are indeed the agents of the sentence’s actions. But it is not always true that subjects name agents. You get to choose which characters you want to put into the subject position.

Some examples:

“All men are created equal.” “Men” are not the agents here—they are not doing the action of creating—but they are certainly characters in that Jefferson and his readers understood men to be capable of acting and being acted upon. So the subject names a character but not an agent/actor.

Another example: “The Dean rejected our proposal because she lacked funds.”

In this sentence, the subject names the agent of the actions, the Dean. But sometimes they do not.

“Our proposal was rejected because funds were inadequate.”

In this sentence, “our proposal” is the first subject, but it isn’t the agent/actor: it doesn’t do the action of rejecting. “Funds” is the second subject but it isn’t the agent/actor either. In this sentence, the subjects are not agents/actors.

Why does this distinction matter? Why not always use people (or people, places, or things) as subjects? The simplest reason is that your readers do not always care about people. Subjects create focus: the subject of a sentence is the main focus of the sentence. When you use a person as a subject, you are creating a text focus on that person. But what if your readers don’t care about that person? They are actually focused on something else? For example, you write “The researcher radiated the cell.” The subject is a person, and thus the subject names a character. But if your readers are focused on the cell, then they will not find the sentence clear or valuable. Consider the effect of repeatedly focusing on something your readers don’t care about. They want to know about the cell and you keep telling them about the researcher. You risk having your work not just seem unclear but unimportant.

If a subject is not necessarily an actor, then what is it? Try to think of a subject as a place, a position in a sentence, one you must fill in in almost all English sentences, and whatever word or phrase you use to fill the position we also call the subject. But the word or phrase doesn’t become the subject because it names an agent, an actor, a character, or anything else. It’s the subject because of its position in the sentence. Consider these 3 examples:

In 1893, Chicago hosted the Columbian Exposition.

Chicago was selected in 1890 to host the Columbian Exposition.

At a key moment in history, Chicago was the site of the Columbian Exposition.

Chicago is the subject of all 3 sentences even though it is the agent of action only in the first sentence. It is the subject because it is in the same position in all three sentences.

To sum up, characters do not need to be the agents of the sentence but they can be if you prefer. You just aren’t limited to that. You choose what characters to put into the subject position depending on what your readers value. More expert readers will probably tolerate and seek less perceptible characters. More general audiences might prefer more perceptible characters like humans, but experts might prefer abstractions because that is what they care about (instead of researcher, they might prefer “cellular secretion of protein factors.”). So long as the characters you put into the subject position are 1) ones your readers see as a character and are valuable to them and 2) are capable of being acted upon or acting, then they can be characters. When we free ourselves of the “subjects have to be actors” or “people, place, or thing,” we find that we can choose effective characters for our readers to insert into the subject position.

Diagnostic #2: Underline subjects. Ask yourself, are these characters to my readers? Do they keep the readers’ focus? Is this what your readers want to read about? If not, consider revising which characters you put into the subject position. If you aren’t inserting characters into the subject position that your targeted readers care about, then your readers will not necessarily care about reading further.

Another tip: Your characters do not have to be identical because that can get boring, but the reader should be able to see the connections between them. Also, try to avoid using 15-word (or lengthy) characters followed by a weak verb.

3. CLEAR AND LONG SENTENCES: The question you should ask yourself is not "how long is my sentence" but "where is all this length coming from"? If the sentence consists of a long string of prepositional phrases, the news is bad. Probably the sentence contains nominalizations that obscure who is doing what to whom. If, however, the sentence contains several subject/verb cores linked by connectors, then the news is probably good, because readers can easily process a sentence – even a long one -- that clearly lays out its characters, its actions, and the logic of its argument.

Instead of a run-on sentence, we can create effective long sentences by using logical connectors and orientors. In that way, one core (subject-verb) can be connected to another core with a different subject-verb but not appear like a list—they will actually be causally linked to each other.

Core: subject-verb. As noted on the other document, ideally cores are up front and close together in the sentence.

Original sentence: The member firms’ individuals or groups designated to choose an exchange as the destination for retail orders are our targets in this phase.

How might you get the verb closer to the front of the sentence?

Revised: Our targets in this phase are the member firms’ individuals…

Tip: Pivot the back end of the sentence to the front!

Orientors: A short word or phrase giving background information before a subject/verb core. When you put a short introductory phrase at the start of a sentence, you can declutter the end of your sentence, which readers find more important. Instead of putting date, location, or time at the end of the sentence, you can often get the core verb closer to the front of the sentence if you use an orientor. In some cases, your sentence will be clearer by using orientors, because they give readers familiar information that they can quickly grasp and then use this information to understand the rest of the sentence.

Original: Suharto resigned after 32 years of rule in a televised broadcast.

This sentence is a bit unclear; would an orientor help?

In a televised broadcast, Suharto resigned after 32 years of rule.

Logical Connectors: Logic words that express a relationship between 2 subject-verb cores.

These words make a causal connection between different parts of the sentence like “in order to” or “even though” or “because” rather than weak transition words like “and” or “or” or “in addition.” (Sample connectors attached)

Cores are discrete thoughts or facts; connectors turn them into meaningful arguments. If your connectors are vague or missing, your entire text will seem rambling, disjointed, impenetrable, or irrelevant.

Logical connectors that say how, why, when, if

(Hint: Download this table to your laptop and try to incorporate more of these!)

|

Contrast |

Time/Place |

Means |

Cause & Effect |

|

but |

until |

how |

because |

|

however |

when |

by |

why |

|

nevertheless |

where |

|

therefore |

|

although |

|

Purpose |

thus |

|

otherwise |

|

so that |

hence |

|

yet |

|

in order to |

consequently |

|

on the contrary |

Time or Cause |

|

then |

|

on the other hand |

as |

Condition |

so |

|

|

since |

if/then |

since |

|

Time or Contrast |

then |

unless |

|

|

while |

|

whenever |

|

Action Verbs: https://www.wheaton.edu/media/education/pdf/whetep-application/2020-Action-Verbs-List.pdf

**Materials for these handout were drawn from the Little Red Schoolhouse, the writing curriculum of the University of Chicago Writing Program.