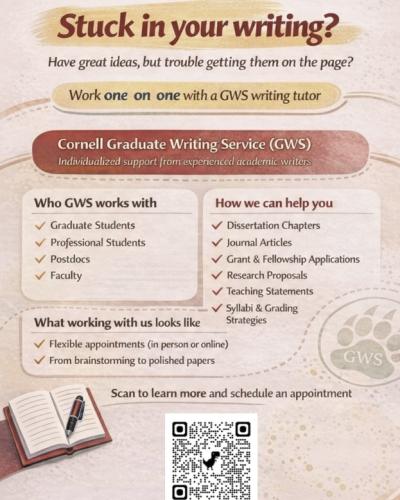

Cornell Writes! Tips from our community of writers is a digital newsletter sponsored by the Knight Institute for Writing in the Disciplines and the Cornell University Graduate School.

Each week, a member of our writing community – a Graduate Writing Service, English Language Support Office, or Cornell Writing Centers tutor; a writing specialist from the Knight Institute; a writing instructor from our First-Year Writing Seminars or Writing in the Majors programs; maybe YOU – will share a writing strategy from their own writer’s toolkit. #writelikeabear

Contact Tracy Hamler Carrick with questions and ideas.

Meet Tracy Carrick

Hello Cornell writers! My name is Tracy Carrick. I am a teacher, tutor, and director of the Knight Institute’s Writing Workshop and Graduate Writing Service. I am also a writer and editor. This week, I am writing letters of recommendations for colleagues and students, and many, many advising emails.

Here is this week’s Writing Tip!

I am a list maker and a list writer.

Like you, I generate lots of ideas when I write, my sentences revealing the spinning wheel of possibilities for where my writing can go, who it can engage, and how it can reflect my desire to be inclusive and far-reaching.

I list so as to reach toward what comes next, to seek complexity, to invite in others and other ideas, to acknowledge what I may not yet know or not yet know how to write about.

I list for myself and for others and for ideas yet to come.

Note here in the three preceding sentences, I have used three different methods for composing lists: syndeton, asyndeton, and polysyndeton. (Yep! This sentence includes another list, this time with a colon, more on that later…)

Did you notice the differences among my opening sentences? If so, did you wonder if you had spotted typographical errors?

As is typical of my posts, I am not offering guidance on correctness. I want to talk about sentence-level style, choice, and control, the oftentimes tacit negotiations we make with our own writer’s voice, our imagined readers, and the ideas we hope to convey with clarity and precision. (Oops, I did it again. Two more lists.)

Let’s take a closer look at syndetic structure.

Syndeton

When writers need to coordinate more than two ideas, we can compose sentences by listing words or phrases, separating the individual items with commas, and placing a coordinating conjunction (usually “and”) before the last item in the list.

Consider my second sentence as an example:

Like you, I generate lots of ideas when I write, my sentences revealing the spinning wheel of possibilities for

- Item 1 – where my writing can go,

- Item 2 – who it can engage, and

- Item 3 – how it can reflect my desire to be inclusive and far-reaching.

Take note of two key features: First, I used “and” only between Items 2 and 3. Second, the items in my list are parallel to each other in both function and form. That is, they offer the same kind of information, and they repeat that information using the same syntactic structure (adjective clauses).

This basic example of 2+ coordination is what most readers expect when they read. It is what most writers are trained to write. Lists are to be closed with an “and.” But that premise, as I discuss next, is actually quite debatable.

Debate about the way I have composed this sentence is more often about whether or not I should use a comma before the “and” (more on the serial comma later), than about whether or not or how I should include an “and” or “ands” in the first place. Let’s explore!

Asyndeton

Notice my third sentence: I use only commas to separate all the items in my sequence:

I list so as

- Item 1 – to reach toward what comes next,

- Item 2 – to seek complexity,

- Item 3 – to invite in others and other ideas,

- Item 4 – to acknowledge what I may not yet know or not yet know how to write about.

Most readers probably want to add an “and” between Items 3 and 4. No thank you! Asyndeton is a rhetorical device, not an error of omission.

In this list, I chose not to close the set of ideas because, as the last item states, I wanted “to acknowledge what I may not yet know or not yet know how to write about.” In choosing not to present the list as complete (as adding an “and” would suggest), I signal to readers that I am not done, and I humbly acknowledge my unfinishedness while also encouraging readers to imagine for themselves what might be added or refined.

Polysyndeton

Polysyndeton is another one of my favorite rhetorical devices. Nope. I did not forget to delete the “and” after Item 1 in my fourth sentence.

I list

- Item 1 – for myself and

- Item 2 – for others and

- Item 3 – for ideas yet to come.

I included that “and” intentionally! Odd? Perhaps. But I enjoy writing and reading polysyndetic sentences primarily because they may draw attention to themselves. They slow things down. They require readers to spend that extra split second to focus on each item in the list. Sometimes, too, I just like the sound of repetition, and the way that the “ands” amble and roll with a different sense of purpose and momentum.

Colons

Another way to slow readers down and showcase your list is to set up a list with a colon as I did in my fifth sentence, as shown here:

Note here in the three preceding sentences, I have used three different methods for composing lists:

- Item 1 – syndeton,

- Item 2 – asyndeton, and

- Item 3 – polysyndeton.

Semicolons

The sentences I have discussed so far demonstrate lists that include relatively simple items. Our punctuation choices get slightly more complicated, though, when our lists include complex phrases that embed details that may require internal commas. Consider this example from a recent text message that I sent to my spouse who was on the way to the grocery store:

In the produce section, you should get six apples, sugar bees or honey crisps; eight bananas, four ripe and four overripe for banana bread; and three pears, but only if soft and fragrant.

I could have used commas instead of semicolons, but the semicolons help clarify which details go with which fruit item as illustrated below.

In the produce section, you should get

- Item 1 – six apples, sugar bees or honey crisps;

- Item 2 – eight bananas, four ripe and four overripe for banana bread; and

- Item 3 –three pears, only soft and fragrant or none at all.

Unfortunately, I did not get these items on my grocery list that day as my spouse quickly scrolled past this bulky text message. Okay. It's true. This is not what a list should like in the context of a text message (more on audience expectations later).

The Comma (Finally, the Serial or Oxford Comma)

Before I conclude, I’d like to consider one additional sentence from my introductory section.

I want to talk about sentence-level style, choice, and control, the oftentimes tacit negotiations we make with our own writer’s voice, our imagined readers, and the ideas we hope to convey with clarity and purpose.

Let’s consider the first list in the sentence here:

I want to talk about sentence-level

- Item 1 – style,

- Item 2 – choice, and

- Item 3 – control,

Some readers will wince at the comma I have placed before the “and” in this list, and that is a fair response. The serial comma, of which I am a devoted fan, is not always a favorable choice or even a disciplinary or professional convention.

I’ve heard many stories about the origins of the serial comma debate, the most interesting and somewhat amusing among them seem to gain traction in the ways they pit groups in opposition to each other.

In one version, publishers of academic presses, initially Oxford Press (thus the common reference to the Oxford comma), have historically included serial commas in style guides. Printers of mass-produced material, on the other hand, have, the stories go, evolved to avoid using serial commas in their desire to save money on ink and/or to squeeze more text into narrow newspaper and magazine columns.

Another version, related no doubt, suggests that the serial comma is a matter of class. People of privilege (so-called elites, those with access to higher education) use them; no one else does. Some even consider serial comma use to be indulgent or arrogant.

Other versions claim the serial comma is only important to writers of American English.

And, finally, in other versions, we see disciplines positioned in opposition to each other with claims that only humanities scholars bother with the serial comma.

I cannot deny that I am likely influenced by some of these narratives. I spend much of my time in the humanities, I have advanced degrees, I write in American English, and I publish most of my writing in academic spaces.

But each time I try to let go of the serial comma, I get stuck in a conversation with myself about clarity. To me, the two sentences below convey very different information:

Version 1 (with the serial comma) – I want to talk about style, choice, and control.

- When I write the sentence this way, it conveys clearly and unambiguously that I want to talk about 3 things: 1) style, 2) choice, and 3) control.

Version 2 (without the serial comma) – I want to talk about style, choice and control.

- When I write the sentence this way, my intentions are not as clear.

- Do I want to talk about 2 things: 1) style, and 2) choice and control?

- Or, do I want to talk about style, more specifically choice and control?

- Actually, neither. Version 1 most accurately captures my intended meaning.

Make no mistake! I am not advocating for or against the serial comma. I trust you and you should trust yourself to use commas (and semicolons and syndetic coordination, see what I did there?) in ways that elevate your voice and ideas, and in ways that make your work accessible to your intended readers.

To conclude, here are three ProTips:

- Keep your eyes open and start noticing what others around you are doing. What do lists look like in the disciplinary, professional, and civic spaces you inhabit? If you are trying to publish, look for a style guide or read recent publications from the publishing houses or journals you are targeting.

- Be consistent with your serial comma decision. Either use it or don’t. It is one thing to make a different choice than your readers, and another to be regarded as sloppy.

- Be playful and selective when you choose asyndeton and polysyndeton for your lists. As with many rhetorical devices, they lose power when writers overuse them. But when used sparingly and with intention, they can enrich your writing and more deeply engage your readers.