Cornell Writes! Tips from our community of writers is a digital newsletter sponsored by the Knight Institute for Writing in the Disciplines and the Cornell University Graduate School.

Each week, a member of our writing community – a Graduate Writing Service, English Language Support Office, or Cornell Writing Centers tutor; a writing specialist from the Knight Institute; a writing instructor from our First-Year Writing Seminars or Writing in the Majors programs; maybe YOU – will share a writing strategy from their own writer’s toolkit. #writelikeabear

Contact Tracy Hamler Carrick with questions and ideas.

Meet Tamar Gutfeld

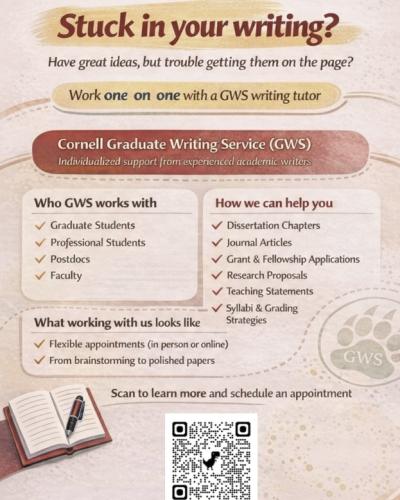

Hello Cornell writers! My name is Tamar Gutfeld. I am a Ph.D. candidate in German Studies and a writing tutor at the Graduate Writing Service. Right now, I am writing a dissertation chapter, applying to fellowships, and teaching German. At the writing center, I enjoy working with students on their dissertation chapters, articles, and conference presentations.

Here is this week’s Writing Tip!

When I get back to a piece I had previously written, I don’t always know where to start. This is especially difficult if there are no comments from advisors, mentors, or reviewers that could help structure the revision process. As Rebecca Schumann once wrote, the hardest part of writing is restarting. Sometimes it seems that rewriting everything or starting from scratch will be a lot easier than revising and editing what I already have. These are a few of my favorite strategies that I use to reignite a writing project.

- Before major renovations, test the foundations!

- Before deciding what needs to be done with your piece, give it a thorough read.

First pass

- Reading without any judgment, take stock: What does this piece of writing already have? What do you like about it? Did anything surprise you about the piece? What did you remember differently?

- It is crucial that you don’t judge your writing – or yourself! – at this point. Imagine that reading this piece is an experiment or part of your fieldwork: you are only gathering data.

Second pass

- Using highlighters or colored pens, separate chunks of writing: highlight the parts that you know you will keep, use a different color to highlight chunks you know for sure will not make the final cut, and a different color to point out the parts with which you are not sure what to do.

- Again – there is no judgment here. You are an architect trying to renovate a structure in the most economical way, keeping as much as you can from the work past you already dedicated. Give past you a high five!

- Do not erase anything! You never know what you will need in the editing process. Sorting the piece into workable chunks grants you renewed familiarity with the piece and gently creates a flexible structure to the editing process. This structure could – and should – shift as you progress with the editing process.

Third pass

- Look at the sections that you highlighted as keepers. Do they have a distinct structure?

- Write out the main idea of each paragraph, together with its function within your piece (Does it introduce a new idea? Does it explain a concept? Does it build up towards an argument?) The main idea and the function of the paragraph should match. If they don’t, make a note, but don’t start editing!

- You now have a reversed outline of the core of your new piece! It may seem that this is a slow process, but it will pay out in the long run.

Working with a reversed outline

- Once the reversed outline is in place, the path to connecting the dots should be clearer.

- Write out extensive notes about what you want to do with each paragraph and section. Explain as if you have to let someone else do the work afterwards.

- Start working on the paragraph you like the most or the paragraph you think needs most work, depending on whether you prefer to poke “swiss cheese holes” or to “eat the frog first.”

- Poking holes in your project, swiss cheese style, means that you go for the easier sections first. Doing that will give you a sense of completion and a motivation boost! Now you have the confidence to tackle more complex sections of the project.

- “Eating the frog” first means that you tackle the most difficult section first. This may be a good idea if you feel that you will continue to avoid it by overworking other sections or entirely procrastinating on the project. Once finished, you know the most difficult part is behind you, and you will have the confidence to tackle the rest of the document!

- One method is not better than the other! Do what works for you, and if it still doesn’t work – try the other method!

- You don’t have to work linearly, but you could if you wanted to. By setting up the structure of the revisions first, you can now focus on whichever part of the piece you’d like. By leaving extensive notes, you know that you can avoid tangents and keep on track.

- When scheduling your work sessions, don’t be tempted to designate entire slots to large chunks, keep it small and attainable!

Creating and working with a reversed outline helps to return the writing to the stake-free, “preparing to write” stage. By engaging and reflecting with what you already have, and assessing each part of the document, you create clear directions and very specific steps for the revisions of each paragraph and section. Zooming out and seeing the bigger picture at the beginning of the process allows you to zoom in at later stages of the process. These clear, small tasks give you a sense of direction and help create very achievable steps that are easy to schedule and feel great to attain.